The society we live in has been built on the foundations of industry. In the North East, our industrial culture and landscape – from coal mining to steel working, textile production to large-scale engineering – has become a significant part of regional identity. Industry has played an important part in shaping our cities, towns and communities, and as a market town, Darlington has a longstanding connection to specialist crafts and trades – from railway lines and shipbuilding to leather tanning and weaving. The sudden process of de-industrialisation in the North East, and the impact this has had on communities and the landscape, has resulted in a growing emphasis on representing and remembering industrial heritage.[2]

However, the growth of industry, and the culture it has fostered, has also played a significant role in accelerating today’s environmental crisis. As we remember and celebrate industrial heritage, its wider impacts cannot be ignored: from the environmental pollution caused by industrial waste to the ‘more, newer and faster’ approach that feeds our disposable culture. More difficult to see, our deference to growth and profit has enabled private sector agendas to hold increasing levels of influence over our landscapes and the decisions we are able to make to combat climate change.

Our time in quarantine has to some extent stalled the wheels of industry and given a brief reprieve to the environment, raising valuable questions about our treatment of the planet and the sustainability of our way of life. Yet this has come with a sudden and painful cost to lives and livelihoods; health, wellbeing and civil rights. A recent study outlined that global carbon emissions as will fall up to 7% a result of COVID-19, if global restrictions remain in place until the end of 2020.[3] By contrast, a reduction of at least 7.6% is required each year for the next 30 years in order to meet the target to limit global heating to 1.5˚C[4], which scientists warn is essential to limit the negative impacts of climate change. Beyond the temporary impact of lockdowns around the world in response to COVID-19, even if global governments hit all our most ambitious environmental targets, global heating is set to rise by more than double this to 3.2˚C[5], with wide reaching impacts on the habitability of the planet.

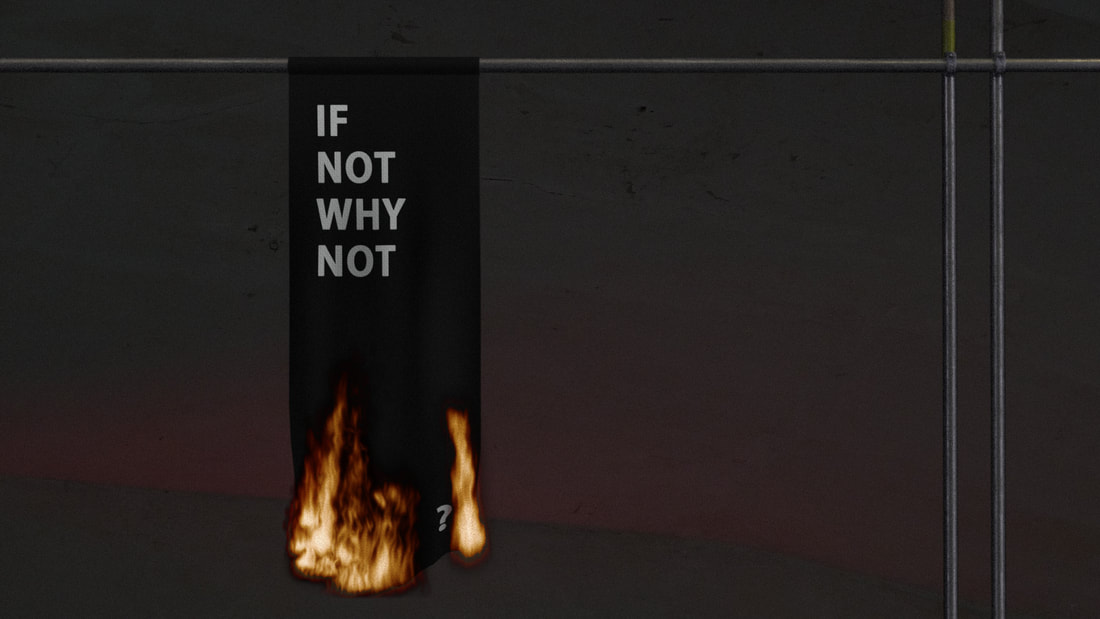

From this vantage point, the scale of the climate emergency seems overwhelming. We can be left feeling unable to make a difference. A feeling perpetuated by negative headlines and the scale at which we have to think: the issue stretches beyond our lifetimes and requires global action to meet the challenges ahead.

Here, building emotional resilience to navigate our internal response is important, because small personal and organisational steps are part of a cultural shift necessary to effect wider change. As individuals and as artists, we can act as climate ambassadors. Through our work, we can create a tipping point in awareness, and share positive and proactive messaging to encourage individual action. Collectively, we must demand better from government and hold them to account. We must change our mindsets and reconsider our current relationships to production, consumption and waste. We must learn to slow down.

Our industrial past (and present) cannot be ignored as we work towards the solutions needed to address today’s climate emergency. We must also consider the role of social justice within our response, recognising that often those least in positions of influence are, and will be, those most affected by its’ impacts. At the recent North East Culture Partnership Forum, VONNE - Voluntary Organisations Network North East - talked about the need for a just transition, recognising that the sudden de-industrialisation of the North East in recent past did not provide adequate time or resources for communities to adapt. This also recognises the imbalance between the capacities of different communities to make these changes - for example, between: rural and urban communities, established and emerging economies, or those affected by historic inequalities.

In all of this, how do we avoid thinking about these issues in a bubble? How do we embed environmental thinking across all of our actions? And with the COP 26 Summit of world leaders – due to take place in Glasgow this November – postponed, and with our public spaces – a shared forum for dialogue and protest – now empty, how do we keep focus?

References

[1] Shantz, J. (2002). Green Syndicalism: An Alternative Red-Green Vision. Environmental Politics, 11, 21-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/714000644

[2] Vall, N. (2018). Coal is our strife: representing mining heritage in North East England, Contemporary British History, 32:1, 101-120. https://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2017.1408541

[3] Le Quéré, C., Jackson, R.B., Jones, M.W. et al. (2020). Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement, Nature Climate Change. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0797-x

[4] UN Environment. (2019). Emissions Gap Report 2019, UN, New York, 26. https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/30797/EGR2019.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[5] UN Environment. (2019). Emissions Gap Report 2019, UN, New York, 27. https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/30797/EGR2019.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

RSS Feed

RSS Feed